Neovim for Unity Dev

My first IDE, like for many others, was Turbo Pascal — the best tool a school kid dreaming of programming could get their hands on. I missed it terribly when I was doing C lab work at university in Notepad.

Then came ActionScript in Notepad++ — thousands of lines of spaghetti code and navigating by line numbers from memory. After that Adobe Flex in Eclipse, then the unfamiliar Objective-C in Xcode. I met the Unity era on macOS with few alternatives — MonoDevelop, which didn’t really click with me. While waiting for JetBrains Rider, I tried to make peace with Consulo — a titanic one-person effort that, unfortunately, lagged behind the big IDEs in stability. As soon as Rider landed on macOS, I became a fan — and pretty much got hooked on the JetBrains ecosystem.

After that, everything flipped: the IDE started choosing the language. I would install GoLand, PyCharm, RustRover first, and only then dive into Go/Python/Rust. The IDE itself helped me learn: before I’d read anything about LINQ in C#, I was already using it confidently thanks to Rider’s hints. I often learned about new syntactic sugar in languages from the IDE. Refactoring was a pleasure, and poking fun at colleagues using VS Code was a nice bonus.

The happiness lasted almost ten years — until I moved onto a large TypeScript project. To be fair, WebStorm wasn’t really to blame: on an aging Mac, build/lint/indexing chewed through memory. As the linter and compiler ramped up, WebStorm would sometimes crawl or even crash, so I had to restart it periodically. But an IDE is a tool that should speed you up, not slow you down. The advent of LSP made comfortable development possible in almost any language in any editor that can speak LSP and handle text well.

Honestly — yes, I fell for the charm of influencers (The Primeagen is persuasive), but even without that I’d been gravitating toward console tools. I gave Neovim a try. There are tons of guides out there on how to turn “that very vi” into a working IDE in a couple of hours, but the real magic is the ecosystem: the community fills almost any need. To avoid drowning in hand-tuning, I started with the ready-made NvChad setup. From there it’s like VS Code: plugins, snippets, extensions. Today I write TS, tomorrow Rust—just by tweaking a couple of settings.

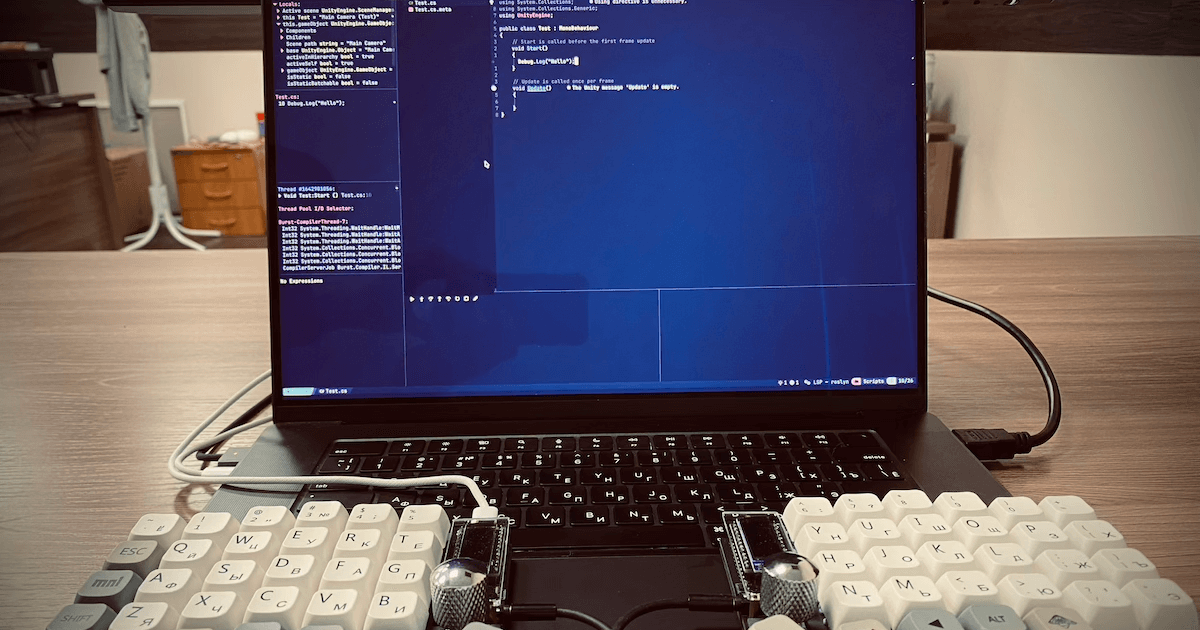

Yes, I had to get a separate keyboard and relearn navigation. But for vim motions it was worth it: fewer distractions — just code and the keyboard.

Now life is steering me back to Unity, and I had a choice to make: go back to Rider (which for Unity “just works”) or keep my Neovim muscle memory. With C# and Unity, getting everything set up is a bit trickier than just “turning on a new LSP,” but the setup came together:

LSP: roslyn.nvim. A fork that works with the Roslyn language server. A modern replacement for OmniSharp.

Debugging (DAP): nvim-dap. To make it work you need to have VS Code installed, which can also come in handy in tough situations (see below).

Unity integration: VS Code as the “official” source of the Unity debugger and for regenerating

.sln/.csprojvia the Visual Studio Editor package (Unity > Preferences > External Tools). Even if I edit code in Neovim, it’s convenient to keep VS Code around as a “service tool” for project generation and, when needed, debugging.

The only thing I couldn’t get working was opening a file in Neovim by clicking from Unity. Not a big deal: I keep the project open in a terminal anyway and jump by symbols using Neovim.

There’s also an “all-in-one” approach: the Unity package nvim-unity makes Neovim an external editor, adds a Regenerate Project Files button, and supports a shared terminal/buffer for project files. On macOS the author asks for tests/feedback, so you might need extra setup out of the box, and it still doesn’t fully resolve debugging.

It’s worth being sober about debugging nuances. The ecosystem around the Unity debugger in the context of Neovim is still catching up with the big IDEs: there are occasional mismatches with the DAP spec, and using VS Code binaries “directly” can run into Microsoft licensing restrictions (some of their debuggers are permitted only inside Microsoft IDEs). So my pragmatic approach is: write in Neovim, and run complex debug sessions through the VS Code/Unity extension.

Bottom line — this stack gives me the main thing: building products without unnecessary distractions. Neovim covers day-to-day development (speed, motions, focus), and where it’s more convenient/reliable, I don’t hesitate to bring in the “heavy artillery” (Rider or VS Code) selectively — as tools, not as a cult.